Harriette Austin Mistress of Mayhem

The Mistress of Mayhem: Harriette Austin

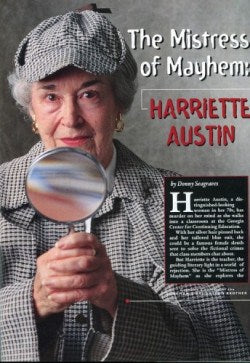

Harriette Austin, a distinguished-looking woman in her 70s, has murder on her mind as she walks into a classroom at the Georgia Center for Continuing Education.

With her silver hair and tailored blue suit, she could be a famous female sleuth sent to solve the fictional crimes that class members chat about.

But Harriette is the teacher, the guiding literary light in a world of rejection. She is the “Mistress of Mayhem” as she explores the darker side of human nature in Murder and Mayhem for Money, her popular non-credit class at the Georgia Center for Continuing Education.

After sharing writer’s market information, Harriette asks the usual question, the one that sometimes causes apprehension in rookies: “Who’s going to read first?”

“I will,” volunteers Jean Stiles, a veterinarian by day and an aspiring author by night, who already has an agent and is writing her third novel.

The class listens attentively as Jean reads from a newly rewritten section of her novel-in-progress. When she’s finished, Jean looks up and asks, ” Do you think that scene was bloody enough?”

“No,” answers Rick Mosley, a former Atlanta homicide detective. “A wound like that would splatter all over, even on the ceiling.”

“Thanks,” says Jean, making notes on her manuscript. “I’ll have to go back and put in more blood.”

Laughter crackles across the roomful of mystery writers. In this class, adding more blood is just another step in an author’s attempt to create a plausible, marketable story.

Many of the group of 20 or so students in Harriette’s Murder and Mayhem class are longtime regulars, including Marie Davis, a librarian at the Richard B. Russell Research Center.

Marie says she can’t imagine her life without the weekly meeting. “I keep coming back quarter after quarter because of Hariette, the other class members, the friendships, the feedback and the possibility that I could conceivably finish my novel,” Marie says.

There are three rules in Harriette’s classes, which include two sections of Creative Writing, as well as Murder and Mayhelm for Money. Class members are asked to make their criticism constructive, to refrain from reading explicit sex scenes in class and never to depict the killing of animals.

This last rule might seem a bit odd in a class where human characters are shot, strangled, knifed and poisoned on a regular basis. But, as longtime class member Beverly Connor explains, killing animals is too often used as a simple device to show how bad the bad guy is. “And that is not good writing,” says Beverly.

“In Harriette’s class we all respect each other’s knowledge and experience,” says Marie. “Harriette respects us as individuals and takes a sincere interest in each of us.”

Feedback and positive reinforcement are keys to the success of Harriette’s writing classes. “You don’t get that from sending your work off and receiving printed rejection forms,” Beverly says.

Although Harriette Austin, a native of Memphis, Tennessee, has spent a lifetime teaching and inspiring writers, in her younger days she never considered either for a career. Instead she dreamed of becoming a scientist.

Harriette’s parents divorced when she was six. An only child, she lived with her mother, growing up in Manhattan and Brooklyn, New York, and Teaneck and Oradell, New Jersey. She was an avid reader of books such as the Hardy Boys mysteries, Zane Grey’s Westerns and Little Women by Louisa May Alcott, a relative on her father’s side.

After earning a bachelor’s degree in psychology from New York’s Barnard College, Harriette moved to Memphis with her mother and stepfather. A year later her stepfather’s job took the family to Hollywood, where Harriette lived for 20 years.

“Some of my friends from college were living in Hollywood and were involved in acting. That’s how I got into it,” remembers Harriette. She studied acting at the Max Reinhardt Theater and was a stand-in for actress Gail Patrick at the Old Republic Studios.

During her time in Hollywood, Harriette married and had a son, Mark Austin Segura. After she and her husband divorced, her life and her financial circumstances changed. “There are things called reversals of fortune,” she says. “You’re looking at a reversal of fortune.”

With the realization that she would have to earn her living, Harriette, then 39, enrolled in the Yale Drama School as a playwriting major. Leslie Stephens, an old friend who was a writer, producer and director of Broadway plays and television series such as “The Outer Limits” and “The Twilight Zone,” had graduated from Yale and had done quite well financially.

“I decided to become a playwright and in doing so I fell into the fallacy that many aspiring writers fall into: I believed that writing would make me rich. But, believe me, it ‘ain’t true,’” Harriette says, laughing.

What Harriette did find at Yale’s famous drama school was a community rich with creative people, such as playwrights John Guare and Oliver Hailey and actors Daniel J. Travanti and Joan Van Ark. She also discovered that playwrights are at the bottom.

“You would think that the most important person would be the writer,” she notes. “Without writers, what would actors act and directors direct?”

At Yale, Harriette worked as a research assistant at the Gesell Institute founded by Dr. Arnold Gesell, pioneer psychologist well known for his studies of the behavior of infants and children. After graduating with a master of fine arts degree in playwriting, Harriette taught drama, speech and English literature at several colleges, including Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College in Tifton.

In the early ’70s, Harriette moved to the Athens area so that her son could attend the University of Georgia. She worked for several years at the Madison County Child Development Center in Comer, taught English at the University of Georgia from 1976 until 1982 and later was on the staff of the Athens Community Council on Aging.

Not long after moving to the Athens area, Harriette had the idea of teaching a creative writing class at the Georgia Center, and she has been doing so since 1974.

Although she bills herself as a creative writing teacher, Harriette readily admits that writing cannot be taught. What aspiring writers need most is encouragement, she says, an environment in which they can test their work in progress without getting hurt by the class’s criticisms.

“But that doesn’t mean you don’t tell people the truth when commenting on their writing,” she says.

“Another thing writers need is persistence,” emphasizes Harriette. “Everybody I know who has become successful has persisted through everything, all the rejections. They fight through their self-doubts. They fight through their husband or wife telling them they can’t write or their children making fun of them. They just do it. And eventually they get published and turn everyone into believers.”

Talent also plays a part in writing success,” according to Harriette. “Somebody can learn to sing,” she says, “but if they don’t really have a good voice, you don’t want to listen to them. Writing is the same. You can learn the mechanics of writing, but you also need the raw material, the talent, to make it work.”

Harriette says she can often spot talent in the very first sentence read aloud. But sometimes it’s not so apparent. You don’t always know what’s there and what might develop.

“There was a man who came into a playwriting class at Yale and read a play he’d written and nobody liked it,” remembers Harriette. “Then later we were shocked to find out he was Eugene O’Neill.”

Hundreds of aspiring writers have passed through Harriette Austin’s writing classes and many of them have achieved their publication goals.

Among them are mystery novelists Ed Wyrick, Beverly Connor and Judy and Takis Iakovou, romance novelist Andrea Parnell, children’s writers Bettye Stroud and Donny Bailey Seagraves and non-fiction author John McCormick.

“We’ve all grown from one quarter to another in Harriette’s class, from listening to each other’s writing to critiquing positively,” says Charles Connor, Beverly’s husband and an aspiring novelist himself.

Harriette doesn’t grade her writing students or require them to turn in assignments or take exams, but tangible proof of her teaching success goes beyond the expanding library of published books, articles and short stories by her students. The annual Harriette Austin Writers Conference at the University of Georgia Center for Continuing Education is a tribute to Harriette and a practical forum for aspiring writers.

The conference, (which is no longer in existence), was founded by Beverly and Charles Connor and Alice Gay in 1994. This year’s keynote speaker (at the time of this article’s publication) is Lawrence Block, award-winning author of over 40 mystery novels.

Clyde Snow, a forensic anthropologist who identified the victims of serial killer John Wayne Gacy, examined the bones of Joseph Mengele and solved the mystery of what happened to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, will also be among the authors, agents and forensic experts at the conference.

“It is very reinforcing to be in the company of people like those in Harriette’s class or at the conference, with people who want what you want,” says Judy Iakovou, a longtime class member.

Judy remembers the first time she ever read aloud in Harriette’s class.

“I was a nervous wreck, like everyone else, I’m sure. And I know my voice was shaking but I couldn’t hear it because my ears were roaring.

“After I finished reading everyone was kind when they commented. When we got up to take a break, Harriette came over to me and said, “You’re a wonderful writer. You don’t need to be nervous.”

“And right then, I was hooked. I just needed to know that I had the potential to get published. I needed to hear that I was a writer from someone I felt knew.”

“Harriette does know,” says Marie Davis, “and we know that she knows good writing when she hears it. That’s why her opinion means so much to us.”

“Affirmation from Harriette goes a long way,” agrees Beverly Connor. “It can cover a multitude of rejection letters.”

This article by Donny Seagraves originally appeared in Athens Magazine.