Harry Hancock Article

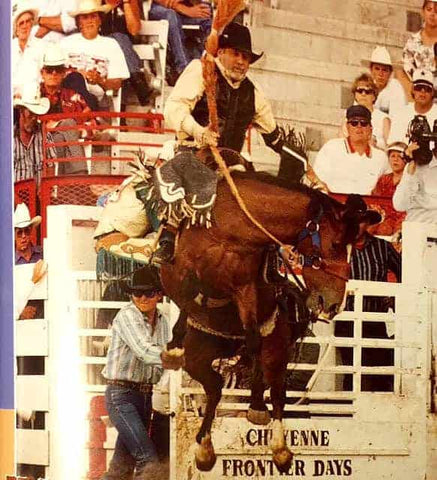

Harry Hancock: World's Oldest Saddle Bronc Rider

Most weekends during rodeo season, Athens native Harry Hancock, 51, slips onto a world-class saddle bronc and rides in front of thousands of cheering fans in a dusty arena hundreds of miles from home.

Holding the bucking rein with one hand and waving the other hand in the air, Harry risks serious injury and even death for eight seconds of glory and perhaps a few dollars in prize money.

In a professional sport where rookies are in their early 20s and 30-year-olds are considered over the hill, Harry is the oldest competing saddle bronc rider in the world.

Why does he do it?

“I’m reckless as hell,” he admits. “Most men my age don’t want to do anything more dangerous than playing a round of golf or sitting in front of the TV, flipping the remote.

“When it’s my turn to ride in the rodeo, I climb onto the back of a 1,200-pound horse and I feel this thrill going through me, a real adrenaline rush,” says Harry. “I nod my head and the gate pulls up and I’m gone.”

For the past three years, Harry has traveled the Southeastern Rodeo Circuit learning his craft and chasing his dream of winning his professional card by earning $1,000 during a season. This year, Harry, who rides as a rookie permit holder, is about $100 away from achieving pro status.

Harry’s dream of becoming a cowboy is rooted in the 1950s. Like most children of that era, he grew up playing cowboys and Indians, imitating Western heroes such as Zorro and actor Roy Rogers. “I always wore boots and jeans and had a Western flavor about me,” says Harry.

At age 13, Harry borrowed money from a local bank and bought his first horse, making payments from his part-time earnings at a grocery store. While living in Bar-H Estates, an east-side subdivision developed by his late father, J. G. Hancock, Harry competed in horse shows. He also played Little League baseball.

Riding horses and playing sports, Harry discovered that his motor skills needed improvement. When his mother, Peggy, enrolled him in ballet and tap-dancing classes at the Moina Michael Auditorium in Athens to improve his timing and coordination, Harry resisted at first. He was one of only two males in the dance class.

Now Harry says his early dance training plays an important role in his ability to ride saddle broncs. A couple of years ago, he took more dance lessons in an effort to improve his riding technique.

“Saddle bronc riding is like a dance,” explains Harry. “Riders must begin with their feet over the bronc’s shoulders. The horse jumps up in the air and bucks and kicks.”

The rider must synchronize his spurring motion with the rhythm of the horse’s jumps in order to stay in the saddle during the eight

seconds required for a score. The rider’s feet are supposed to be straight out in the front when the bronc’s front feed hit the ground. They should strike the back of the saddle, knees bent, when the horse next lunges into the air.

“If you can stay in time with the horse, saddle bronc riding is easy,” notes Harry. “But once you get out of time, it’s like a bumpy dirt road.”

Harry, who today resembles actor Clint Eastwood more than ballet dancer Mikhail Baryshnikov, can still tap dance, although he says with a grin, “Don’t spread that around too much. Real cowboys don’t dance. They Ride saddle broncs.”

After graduating from Athens High school in 1965, Harry attended Gainesville College before joining the Army and serving a year in Vietnam. Eventually, he followed in his father’s footsteps by starting his own construction company.

An avid hunter, Harry began making yearly trips out West with friends to hunt big game. A few years ago, he moved to Colorado and lived there for a year. He met some “real” cowboys for the first time in his life and they took him along on cattle drives where he learned how to pack mules, ride a trail and live the “cowboy life” he’d dreamed about as a kid.

“It was the greatest experience of my life,” says Harry. “The cowboy life is so trouble free. It’s so much less pressure. You don’t have any problems if you’re a cowboy. You don’t have any money, but you don’t have any problems.”

After he returned to Athens, Harry continued his interest in hunting. On the way home from a hunting trip, he stopped at a rodeo in Covington. Watching the bull riders, Harry decided that he could ride bulls too. He got on a bull for the first time at age 49 and rode him better than the cowboys he’d been watching.

“I was hooked on rodeo after that,” says Harry. “I rode bulls for about a year — until I fell off of one and broke my collarbone. That’s when I switched to saddle bronc riding. At least they don’t come back and try to eat you while you’re on the ground.”

Saddle bronc riding, which is considered rodeo’s classic event, developed in the 19th century as ranch hands in the Old West broke in horses for ranch use. Saddle bronc riders today are judged by how well they ride and by how hard the horse bucks.

Riding saddle broncs is more difficult than bull riding and it’s harder to learn, says Harry. “But once you learn how, it’s easier, especially on your body. This is a better rodeo event for a man my age.”

Because of his age, when Harry first joined the rodeo circuit, he wasn’t taken seriously by rodeo officials or the other cowboys who wondered aloud why a 49-year-old man would even want to compete in the physically challenging sport of rodeo.

But after they watched Harry come back from injuries and continue to compete, they began to respect the cowboy with the gray beard and the unwavering determination to achieve his goal of winning his pro card. Announcers began complimenting him when it was his turn to ride, calling him the “Dirt Devil” from Athens, Georgia, referring to his underground utility business in which he “digs dirt.”

And best of all, the other cowboys began to respect Harry, which helped fuel his own determination, not only to ride but to master the sport.

“I’ve developed a real drive to succeed,” says Harry. “I’m hardheaded. I’m going to prove that I can do what I want to do, no matter how old I am. I’m not a serious contender because of my age. But I’ve never quit anything before in my life and there’s no way I’m going to quit rodeo before I win my pro card.”

Like other cowboys, Harry selects the rodeos in which he wants to participate by consulting the listings in the weekly publication, Prorodeo Sports News. He pays an entry fee, which averages about $55, and calls a week before the rodeo to see which horse he has drawn. He has the option to decline the horse but says he has never turned one down and has ridden nine out of the top 30 saddle broncs in the world.

As a part-time cowboy, Harry rides mainly in the Southeastern Circuit. Throughout the year, these cowboys compete for points that go toward their place in their circuit standings and in the world rodeo standings.

In an effort not only to ride saddle broncs but to improve at the sport, Harry constructed practice chutes at his farm in Watkinsville. Using horses loaned on a rotating basis by a stock company, he practices saddle bronc riding two or three times a week.

In addition to his practice rides, Harry exercises and lifts weights to keep in shape. “I have to work out every single day,” he says. By staying in good physical shape, Harry, who has been knocked unconscious five times during rodeo performances, minimizes injuries when he falls.

The cowboy is a living legend, a rich and romantic part of American heritage. With three years of bull and bronc riding under his belt, Harry Hancock considers himself a genuine cowboy.

He explains his concept of a cowboy in the ’90s this way: “A cowboy is a kid who’s got a dream to compete in the rodeo. You’ve got your barroom dancing cowboys and your country music singing cowboys, but they’re just putting on a show.

“Real cowboys ride in the rodeo. They ride bucking horses. They’ve got a dream and they get out there at the rodeo and try to accomplish that dream. They work real hard at it even thought they are the lowest paid athletes in the world.”

But that doesn’t stop real cowboys from competing in the rodeo. “Because the rodeo is not about money. It’s about accomplishments and dreams,” says Harry.

Rodeo is one of the cleanest sports around, according to Harry, who has been to over 500 rodeos in the past three years and has never had anything stolen. Drug and alcohol problems are minimal. And, according to Harry, there is an unwritten “cowboy code” that most cowboys live by.

“Cowboys help each other,” says Harry. “It’s not who beats whom in rodeo. It’s who beats the animal. Cowboys are interested in everybody having a good ride and in nobody getting hurt. They’re not interested in who wins what. That comes at the end of the rodeo.”

Harry’s wife of 29 years, Sandra, and their son Harry Jr. and daughter Heidi all support his rodeo career and watch him ride in the Great Southland Stampede Pro Rodeo in the University of Georgia’s Stegeman Coliseum, sponsored by the UGA Block and Briddle Club each spring.

Although Sandra admits to being a “rodeo widow” and worries about Harry getting injured, she is rooting for him to win the pro card that would allow him to enter some competitions that are closed to rookies.

“To ride the rodeo circuit at my age — or any age — takes dedication and ‘wannabe,’” says Harry. “You’ve got to wanna be a good rodeo athlete. You’ve got to want it more than anything in the world.

“I’m not going to quit riding saddle broncs after I win my pro card,” declares Harry. “I’m going to ride until I’m at least 55. And I’m going to keep getting better at bronc riding. I don’t want to just go to the rodeo and be the 50-year-old guy who comes out and rides a bronc pretty good.

“I want to keep practicing until I’m the old guy who shows up and people watch him ride because he can really ride the snot out of that horse.”

Note: After this article appeared in the Athens Magazine, October 1997, VOL.9 NO. 4 issue, Sandra dyed Harry’s gray hair and beard and he won his pro card.